What is an MCL Tear?

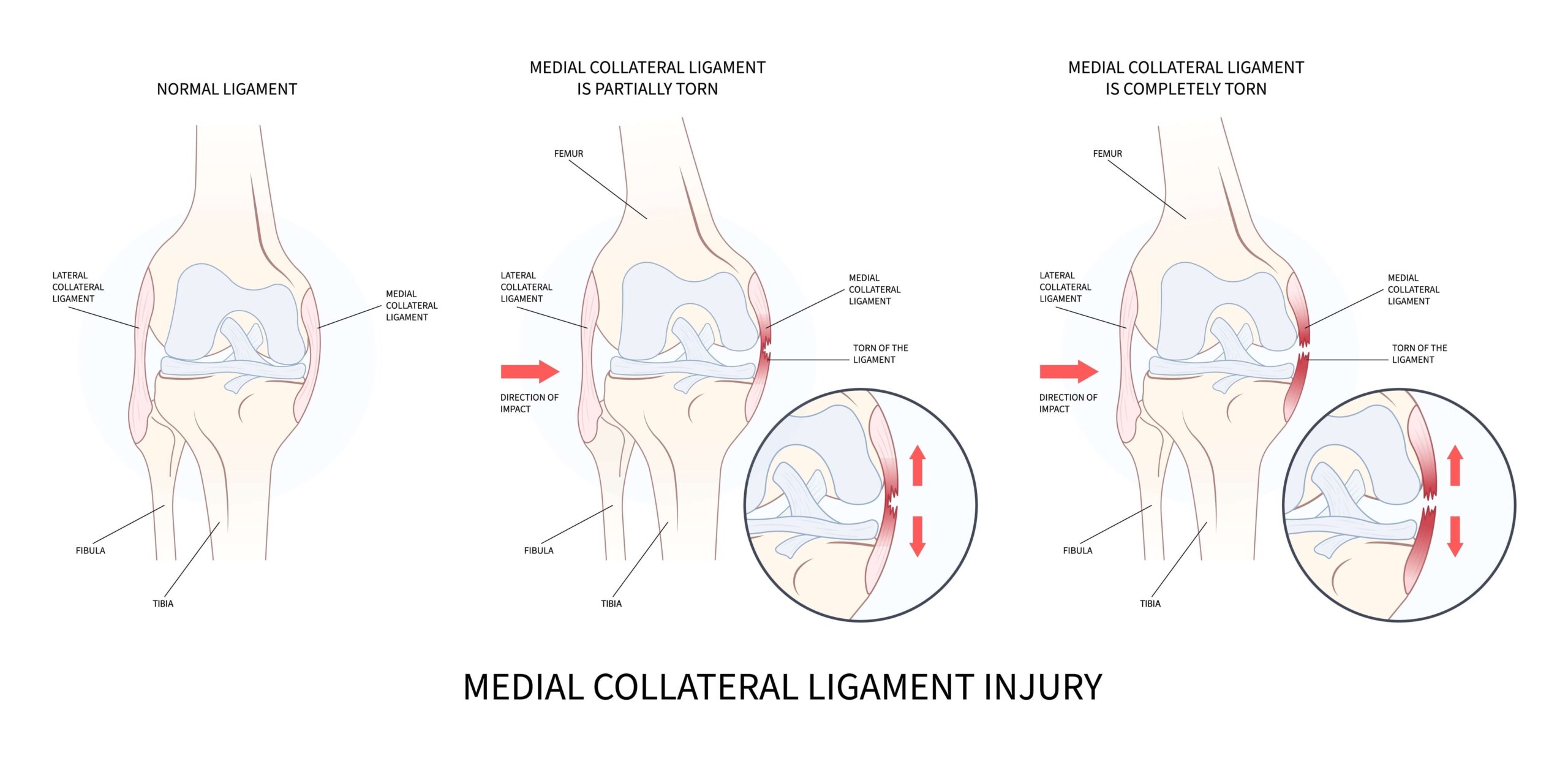

An MCL tear occurs when the ligament is overstretched or torn due to sudden twisting, direct impact, or a change in direction while the foot is planted. Some people may even hear or feel a popping sound. The severity of an MCL tear can vary from a mild sprain (Grade 1) to a complete tear (Grade 3).

Symptoms of an MCL tear include:

Instability or a feeling that your knee may give way.

MCL tears can occur in isolation, but they are frequently involved in combination with injury to other structures, such as ACL and meniscal tears.

Does my MCL tear need surgery?

Thankfully, most isolated MCL tears can be treated without surgery, particularly if they occur at the proximal (femoral) end of the ligament. Physiotherapy to reduce pain and swelling, improve the range of movement, and strengthen the knee joint enables most people to return to being fully active. Some people experience persistent feelings of instability in the knee despite excellent rehab, and surgery may be needed.

Early MCL repair

Sometimes, I meet a patient with significant laxity in their knee when the knee is in an extended position. This usually means they have a distal tear (i.e. the tear is at the tibial end), and the tendon is completely pulled off the tibia. The blood supply of the ligament in this area is poorer, and the surrounding tendons (pes anserine) stop it from healing properly. In these situations, it is best to surgically repair the tendon as soon as possible, ideally within the first three weeks from the time of the injury. If the MCL tear has happened along with an ACL (Anterior Cruciate Ligament) tear, and if the ACL has torn very close to the femoral (upper end) attachment, it may be possible to repair both the ACL and the MCL very soon after injury. However, at the time of the surgery, if the tissue quality of the ACL is poor, I may need to reconstruct rather than repair the ACL.